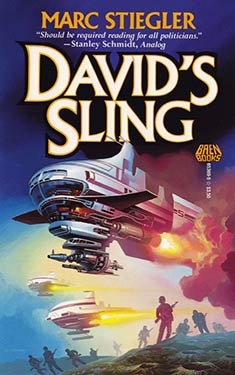

David's Sling

| Author: | Marc Stiegler |

| Publisher: |

Baen, 1988 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

A team of superior U.S. hackers seeks to develop computer-controlled smart weapons for use against a hostile power, but the team members find they need a greater understanding of the problem itself as they search for a way to end a war between two superpowers without destroying the planet itself.

Excerpt

April 18

All side effects are effects.

We can never do merely one thing.

--First Law Of Ecology

Glare. Howling wind. A rope sliding upward in the snow. Sharp-cut steps in the mountainside. His leg straining to take that next step. Hilan Forstil knew nothing beyond that next step. He balanced on the dull edge of unconsciousness, yet he took that next step. And the next.

He remembered this feeling from long ago. The feeling was one of exhaustion--an exhaustion so deep that even the thought of death did not bother him. The memory came from a time over two decades in his past--from his time in Nigeria, working among starving children.

Such exhaustion made one sloppy, he knew. And such sloppiness was dangerous in struggles like this. The danger to himself didn't bother him--after all, he didn't care if he died--but it disturbed him that an error here could kill his rope partner.

On the other hand, it was her fault that they were here at all. An image flashed in his mind of Jan's face at their last rest stop. The flush of her cheeks, the brillJant of her blue eyes... her energy seemed too intense to be healthy. Dimly, he remembered having had such energy himself, standing at the base of the mountain. But the mountain and its vertical miles of glacial white had consumed him. It had not consumed her.

He wanted to curse her.

And he wanted to thank her. With every step he completed, he touched an inner power he had forgotten. He had worked so hard the last two decades to forge the tools of external power; such tools seemed fragile now.

The rope slackened. Hilan breathed a sigh of relief and slowed to match the speed of the rope. Keep the rope just barely dragging the ground between us, Jan had explained the day before, except during a--the rope yanked taut, causing Hilan to stumble--switchback!

He peered up. Sure enough, the chiseled footprints went on to his left for a short time, then veered back sharply to the right. Jan was directly above, climbing to the right with a cougar's enthusiasm. He couldn't go all the way around the switchback even if he had the energy: but if he continued to the left, the taut rope would drag Jan back as well. He took one more pressure-breath and shakily climbed straight up the mountain, shortcutting through e switc .

Noticing the jerking motions of the rope, Jan stopped to look back. Her mouth dropped open. "Hilan," she called loudly, "you can't--"

Hilan looked up at her, just as the snow yielded beneath his foot. He plunged through the snow bridge into the crevasse beneath.

The rope snapped taut, bouncing him wildly on the end. The plunge halted only a moment before he plummeted again and the rope slid farther ever the edge. He looked down into the shadowy cavern below, interested but not afraid. The all-crushing fatigue numbed his mind; he just didn't care. He contemplated his own emptiness, knowing that his lack of fear should be the greatest cause for fear.

His descent slowed, then stopped. He swung lazily in the endless, rocky fracture, listening to the sudden quiet. A wheezing cough echoed down from above. Hilan pictured Jan on the edge of the precipice, leaning into her ice axe with all her-strength to stop the fall. Both their lives depended on her endgranqe.

The realization of her danger finally impelled him to action. Miraculously, his ice axe yet dangled from his right wrist. He pressed his lips together for an explosive series of breaths--the whistling sound seemed almost natural now--and wriggled his ice axe into his backpack straps. He grasped the rope. The fatigue yielded to a last buildup of adrenalin.

He climbed over halfway up the rope before the adrenalin failed.

He clung to the rope, thinking about the danger to Jan. If he could not complete this climb, he had to save her. He still had his knife. He could cut the rope, freeing her from his own fate. He would save enough strength to complete that last act, if necessary. But he was not that lost yet, not quite yet.

Shadows. Deadly quiet. A rope anchored in the snow. His left arm stretching to grasp the next handheld. He balanced on the dull edge of unconsciousness, yet he took that next handheld. And the next.

The rope ended. Hilan reached over the lip of ice, heaving himself out of the crevasse into the glare and the howling wind.

The two-man celebration began with champagne. "A toast to the Soviet Union!" Jim Mayfield exclaimed, raising his glass.

Earl Semmens raised his as well; the glasses tinkled in midair. "A toast to peace," be offered.

"And above all, a least to tomorrow's Gallup poll results." Mayfield sipped the champagne. His eyes slid across the floor, lingering on the emblem woven with rich blues and golds into the carpet. It was his, at least for now. The emblem was the ofiicial seal of the President of the United States. He sat back down; the Secretary of State followed his lead.

Earl sat on the edge of his chair, staring out the window. He spoke in rehearsal of his planned statement to the press. "Yes, this treaty is another potent lever against the arms race. Now that we've curtailed the space-based Ballistic Missile Defense work, all incentives for building new missiles will disappear." He turned back to Mayfield, and for a moment his pudgy features held lines of worry. He tapped a nervous finger on the president's desk. "I wish they hadn't instigated that... little incident in Honduras just before the signing. God, they know how to goad us!" He shivered, then resumed his nervous tapping. "Well, we couldn't have done anything about that anyway, regardless of treaties. And the treaty's more impartant." He nodded his head, and his voice again sounded press-ready. "Yes, the whole world can sleep more securely now that the arms race in space has stopped."

Sometimes the elegant power of the Oval Office gave Jim a sense of grandeur. Seated behind a desk of massive proportions, a desk to dwarf even giants, he felt the ramifications of his decisions pulsing through the world. "Not quite everybody will sleep more securely, Earl. Those goddam contractors working on space weapons will have to find an honest way to make a living." He rubbed his hands. "We may balance the budget yet, Earl." He breathed a sigh of exultation. "Wouldn't that make a hit on the polls."

The door from the Rose Garden swept open with smooth, decisive authority. Even without looking, Mayfield knew who it had to be--though he could not prevent himself from shooting a frown toward the door.

Only one person other than himself entered this room as if she owned it: Mayfield's Vice President, Nell Carson. Mayfield smiled blandly, confident that his irritation remained hidden. Watching her look back at him, Jim saw that Nell had no intention of concealing her irritation. It poisoned the joy of his celebration.

Sometimes the elegant power of the Oval Office gave Jim a sense of claustrophobic choking. As Nell looked at him, he felt a brief desire to plead that it wasn't his fault, whatever had happened. His eyes returned involuntarily to the emblem in the carpet; it reassured him.

Nell stepped to the center of the room to address both men. She spoke with tight control that did not reveal her gentle South Carolina accent. "Congratulations, Jim. You have the record for the most treaties with the Soviet Union in the history of American presidents. I have one question."

Jim looked up into her face, searching for the Nell he had known during the campaign--the Nell with the patient smile who had charmed the crowds with her enthusiasm and warmth. She had been a terrific asset during the cmnpaign. When she spoke, the voters believed.

Unfortunately, the charming Nell had faded under the weight of office. Now he could only see the Nell who had devastated opponents with her incisive criticisms. Jim's throat felt dry as he filled the silence. "Yes? What one question do you have?"

"Now that you have set the presidential record, I was wondering: Can you stop now?"

Mayfield's smile turned gray, and his heart missed a beat--something it did more often now than before, something he should check... He excised the thought from his mind, removing it with surgical perfection, and reluctantly met her gaze, contemplating her question, looking beyond it to her problem.

Nell Carson was the problem, he decided. She never took a moment to look at the bright side. Perhaps that explained the drawn lines in her face. During the campaign, the only objection the media had raised about Nell was that she was too young. She had looked too young. No one said that any longer. Mayfield sighed. "Why do you always complain about our successes? You know we needed that treaty. We had to get that treaty. Our position with the public was slipping." He shrugged. "We have to depend on treaties, not weapons, if we're going to have a chance of dealing with our domestic problems."

Nell looked into his eyes. It seemed Jim could hear his words echoing back to him, amplified and clarified by Nell's implicit interpretation. She asked, "Who are you trying to convince?"

Mayfield stared at her in amazement. "I'm convincing the public, of course." Her hawkish glare made him shiver. "If I didn't know better, I'd swear you were a Republican!"

A tight smile crossed her face. "Perhaps I should be." She leaned over Jim's desk. "Don't you see the problem with what you've done? Six months ago, you made the agreement on Global Consequences of Nuclear War. There you agreed that, above a certain level of nuclear war, the radiation and climate of a war would destroy the attacker, even if the defender didn't shoot back. Now you put a limit on Ballistic Missile Defense. Either one of these treaties, all by itself, is okay. But when combined, they form a terrible danger. Don't you see how these separate agreements interact?"

She paused in her speech. A stiff creak announced Earl's attempt to shift his chair away from her.

She did not relent. "Winning an all out war now sounds believable. Without any missile defenses, but with an agreed threshold for nuclear suicide, the first side to launch its missiles is protected from retaliation--because the first strike will deliver as many megatons of destruction as the Earth can absorb. If the victim shoots back, he's destroying whatever survivors remain in his own country."

Mayfield waved the objection aside. "Don't be boring; we've discussed this a million times. The Russians don't think that way. That would be the attitude of a madman!"

"That would be the attitude of a terrorist," came Nell's curt reply. "With strategies based on terror, only terrorists have a chance of winning." Her eyes swept over both men. Jim shivered.

Neil's mouth softened into a sad smile. "And I don't see a single terrorist in this room. I don't even see anyone willing to speak out about clear violations of national boundaries--like the fiasco outside Yuscaran."

Jim looked speechlessly at Earl. He felt like cement cracking under the weight of a speeding truck. "How did you find out about that?"

Nell laughed joylessly. "You sent me to Texas to give Kurt McKenna his medal, remember? I have the clearances, Jim, and under the circumstances, I had suflicient need to know." She lifted her briefcase and thumped it against the polished mahogany surface, making Jim wince. With forceful snaps, she released the latches and removed a television with a tiny video player. "I think you should see this for yourself, Jim."

He had no time to object before the tape rolled into action.

They were traveiing down a twisting trail, cloaked in juggle growth. It looked like a sticky, humid day, which made Mayfield appreciate the cool comfort of the Oval Office. He could hear tracks clanking in the background, though the sound was muted. Ahead of them on the trail was an armored vehicle. Mayfield wasn't sure, but he thought it was probably a Bradley armored personnel carrier. He vaguely remembered authorizing a few for the Hondurans.

Nell acted as commentator. "We're watching through the gun cameras of a personnel carrier," she explaiped.

A dull explosion sounded, and the screen washed out in a searing white flame. A scream came from very close by. With a chill, Mayfield realized that there had been people inside the machine now turning into an inferno.

Nell spoke with dry, scientific precision. "They hit the Bradley with a shaped charge. The penetrating explosion hit the ammunition magazine. The brightness of the explosion severely damaged our gun camera; the rest of this tape has been computer enhanced."

The whiteout of the screen faded; a ghostly soft image replaced it. Men scurried into the jungle as the second Bradley disgorged its troops. The computer enhancement kept the soldiers visible to Mayfield's untrained eye, though he suspected that without the computer's intervention, they would have disappeared in the heavy foliage. They all looked like Honduran troops.

One Caucasian stood out by virtue of his uniform and his pale blue eyes. He took off with astonishing speed, loping over the fallen trees, hurrying away from the others. The camera lurched as another explosion sounded, muted, but somehow closer. A sound he had not noticed before stopped--the sound of an engine thrumming. He could not see it, but Mayfield realized that the Bradley from which they watched the scene had been hit, though the camera continued to roll.

The focus shifted to another ragged cluster of men with machine guns, beyond the burning Bradiey. Their seemingly random pattern proved quite methodical. They engaged the scattered Honduran troops one handful at a time, overwhelming them piecemeal.

Something seemed wrong with this battle. Mayfield asked, "Where's our air cover?"

"Our helicopters are old and tired, Jim. They're too dangerous to use in battle."

"What about artillery support?"

"We were using our newest radios for communication. They're very delicate, it turns out--oh, the boxes are mil-spec and indestructible, but their frequencies wobble and they get out of tune all the time. So nobody heard about the ambush until it was over." She paused, then ended. "I asked Kurt about it at the reception. He didn't exactly answer me; I suspect he couldn't say what he wanted to in civilized company. Instead he very politely told me that he was getting out of the army--that he intended to get as far away from it as he could go."

Only a couple of Honduran troops remained, hunched in silent fear behind trees and rocks. Suddenly another explosion sounded and half the enemy force fell to the ground. The other half dived for cover. They started shooting in several different directions, though no targets were visible. The gunfire achieved a syncopated rhythm, and continued for a time. One by one, however, the enemy troops twitched as if kicked, then stopped firing.

When just a few enemy troops remained, a long, camouflaged blur leaped out of the brush. "Kurt McKenna?" Mayfield asked. Nell just nodded.

A scuffle followed, then shooting, and Kurt spun down, struck. One of the two surviving opponents lifted his pistol, but McKenna rolled again, and the enemy with the gun went down.

The computer enhancement zoomed in on this struggle between the last two men--the one with the pale blue eyes and the other with... the other one also had pale blue eyesl

"Who is that?" demanded.

"That's the Russian who organized this little party. Didn't you know? You authorized classifying this skirmish, so that no one would find out about the Russian involvement."

"Oh my God." Mayfield had classified it because it was too embarrassing, not because of any Russian involvement. Perhaps he should have read the report after all.

"To my knowledge, this is the first time Americans and Soviets have met in combat in this decade."

It wasn't a fair fight--Kurt had lost the use of one arm when he was shot earlier. Yet a few seconds later, he was the only one left standing.

Nell shut off the tape. Her voice changed from analytical to commanding. "Jim, we can't sign any more treaties like this last one."

Mayfield shuddered. But he couldn't let Nell Carson, or even some incident in Central America, interfere with the main task. The next election was only a year and a half away. He leaned back in his chair. "Don't worry, Nell. Everything's under control."

For just a moment, Nell's shoulders sagged. Then she straightened and headed for the door. "I'm counting on it," she said, leaving as abruptly as she had arrived.

After a long moment, President Mayfield turned back to the Secretary and spoke quietly. Each relaxed into a smile. Earl popped another mint in his mouth, and Mayfield accepted one as well. The celebration continued.

They reached the glory of the mountain's peak. Hilan reveled in the view; his joy seemed too great for a single person--it bordered on reverence.

Below, sunlight chased itself up glacier-white slopes. The streaks of brilliance followed his own path, up from the clouds that clung low to the mountain's side. Above, a single white wisp of cloud traced across deep blue skies. The blue had a sharpness that comes of air too thin to fill a man's lungs.

Earth lay across the horizon, beyond a pillowecl carpet of clouds. Only the grandest features revealed themselves at this distance. The planet did not seem small, yet it seemed conquerable, as this mountain had been. Hilan realized with hope that indeed mankind had penetrated the most dangemus places the planet offered. Yet he despaired, remembering that now the descendants of those explorers were themselves the greatest remaining threat.

Hilan had changed in the years since his service in Nigeria. He had changed most during a trip there several years later. Starvation no longer occurred frequently enough to cause a global reaction, but it continued; malnutrition hid in every shadow. The population had grown. Hilan realized that for every ten children he had saved, eleven would now die. Yes, Hilan and the others had held famine at bay for a moment. But they had not changed the culture that made famine possible. In some final analysis, his had ended in failure.

His friends had rejected his analysis. He had tried to reject it as well, but he could not.

He had entered politics, believing that better solutions to the problems of mankind would require the accurate application of power. He did not yet know how to apply that power. Probably no one did. But for the moment, he would work to consolidate the power, in preparation for the day when he, or someone, learned how to use it.

Jan led him down the slopes to a shallow depression. Short ridges ringed it on three sides, protecting them from a bitter wind as they made camp. She borrowed his swiss army knife to slice open their freeze-dried food pouches, then started pacing between the packs and the stove to prepare dinner. Her cheeks glowed with an energy that struck Hilan again as somehow too fierce, too burning for a healthy woman. "Believe me, it's much easier going down," she promised him. "If this hadn't been such a great campsite, we could have gone all the way down the mountain today with no problem."

Hilan groaned softly and lay on his sleeping bag. Only his eyes moved, watching Jan pace.

"So, are you happy you came along? I am." Jan turned away in a fit of coughing. When she turned back, the flush of her cheeks had faded. She handed him back his knife.

Holding it, Hilan remembered his earlier desperate thoughts to save Jan if he could not make it. "When I stepped into that crevasse, I almost killed you. I wonder whether it makes sense to rope people together--whether it wouldn't be smarter to sacrifice the one who falls to guarantee that someone survives."

"Nonsense. Falls like that remind us why we wear ropes and why we make everyone on the climbing team interdependent in the first place. I'm just glad we responded effectively to the crisis."

"Did we?" Hilan stared at the rips in his gloves, cut during his climb up the rope. "You know, I was so tired before we even reached that crevasse that I hardly noticed the fall." Thinking about it, he was there again. "It was really strange, just staring down at the rocks that would kill me." His eyes unfocused. "I didn't react correctly at all."

Jan laughed. "Hilan, you had the perfect reaction--no reaction at all. I wouldn't worry about it."

Hilan grunted. "You're probably right. I'll miss the switchback over and over, each time reinforcing the lesson that I learned. In fact, I'll learn the lesson far better than if I'd simply gotten scared when I fell. It'll make a great reinforced revelation. Sounds like a good example for you to teach at your beloved Institute."

"Yes," Jan said softly, "an excellent example."

Hilan exhaled. The air rushed from his lungs with the easy freedom that reminded him how high up they were. He had never thought of breathing as an effort, or of the friction of the air upon his throat; now, in their absence, he knew them.

"Jan." His muscles still hung in limp exhaustion, but his thoughts raced. "Thank you for bringing me here. In my role at home, I've welded myself so deeply to my senatorial image that sometimes I wonder whether I'm still here, or whether I'm only an image. New I know."

"I thought you'd like my mountain." She coughed. Hilan studied her for a moment. Her flush from the climb had faded. Now she seemed pale--as much too pale as she had earlier seemed too flush. "I have a favor to ask of you."

He sighed. "You know how to exploit even a moment's weakness. What do you want me to do--help you save the world?"

Jan gave him an expression of surprised pleasure that would have fit well on an American in the Orient who rounded a corner and ran headlong into an old high school chum.

That reaction pleased Hilan immensely. Jan did not understand him as well as he understood her.

Even among his old friends, Hilan had been surprised by how rare and how out of place the people who personally sought ways to save the world were. Even Hilan's wife did not understand this fixation of his on the problems of huge scale--questions of famine, of economic collapse, of nuclear war. Jan, like himself, was one of those very few who thought in such terms on a daily basis.

But Jan was an even rarer breed of human being than those who sought answers to the big questions--she had found some answers.

She had not yet solved any of the big problems, but she had begun to heal at least one medium-size one--she had synthesized a therapy that could usually cure the most common American addiction: cigarette smoking.

Jan continued. "I don't know whether the favor I'm asking you will help save the world or not. Perhaps it will. I wish I knew." Another cough punctuated the sentence. "What I want you to do is talk with Nathan about the Sling."

"The Sling?"

"Yes. It's E military research projeqt."

Despite the exhaustion, and the stitfness of his skin from cold and exposure, Hilan managed to grimace. "God, I hate the military." Again, the air left his lungs too fast. "I wish we didn't need it."

Jan smothered a laugh. "Our mammoth military-industrial complex isn't very American, is it? You know, the first act of the American government after the Revolutionary War was to disband its standing army. They sold the navy's ships. America's forces were reduced to 80 men, none above the rank of captain."

She stretched out on the sleeping bag beside him. "Even today you can see the strength of the anti-military roots of our country. How else could America engage in fierce public debates over permission for advisers to carry sidearms? Even at the heights of our military adventurism, an astute observer can see that it's unnatural for us: we do it so badly. We make better businessmen than soldiers."

Hilan had never thought of it in quite this light before. "Yet America wound up as the principal adversary of the most powerful military force in human history." He thought about the absurdity of the situation. "How did we get ourselves into this position?" He shook his head. "Even more important, how have we managed to pull it off for such along time?"

"For decades, we succeeded as a superpower by holding the ultimate club. We succeeded because we had more, and better, nuclear weapons." She shook her head. "But that doesn't work anymore. How could we convince a cold-eyed political pragmatist like Sipyagin that America would use nuclear arms, knowing that the Soviets would destroy us in turn? The nuclear threat served us well for a long time, but its time has come to an end. No one believes we can use it anymore."

Hilan on his bag, trying to burrow into it. The chilled air made the goose down warmth precious. "It's impossible for anyone to believe that we'd use nukes as long as Mayfield is the decision maker. Some people have trouble believing he can use a letter opener, much less a nuke." Hilan tried to say it without passion. President Mayfield was a member of his own party, after all.

Jan nodded. "You know, both the Soviets and the Americans go through cycles of confrontational behavior. You might think the greatest danger looms whon both countries reach the peak of their aggression cycles at the same time. But that's not true. The greatest danger occurs when the cycles go out of phase--when the United States reaches one of its lowest lows and the Soviet Union reaches one of its highest highs."

The cold of the glacial air reached Hilan's heart. "And we've come to that moment in the cycle."

Jan didn't answer.

"So what's the Sling Project?

Jan laughed at the compound of despair and hope in his voice. "We make better businessmen than soldiers. We must fight, then, as businessmen."

Hilan tried to snort, but it took too much "A division of businessmen wouldn't last very long against a division of soldiers."

"No, of course not. We'd still need soldiers. But we can do with a lot fewer soldiers than some countries because we have another strength: we have crossed the threshold one form of society to another. Our oppouents live in the Industrial Age. We stand on the brink of the Information Age. We must build an Information Age system to defend ourselves."

"And just how do we that?"

Jan smiled at his limp form. "You look so exhausted--and so curious at the same time. I think I'll leave you in this state and let Nathan tell you the rest of the stoyy."

Hilan groaned. "Very well. When would you like to introduce us?"

Jan closed her eyes. "That may not work," she said. She coughed again, and this time it racked her whole body. Blood spattered the soft snow, a dark obscenity in the evening sunlight. "Dammit," she muttered, "I better at least get off the mountain."

Hilan rose unsteadily to his knees. "What's wrong? What's happening?"

"I'm really sorry, Hilan. The climb down may be harder than I'd hoped.

"What!?"

Jan rose to her feet and put her hands on his shoulders. "Hilan, you're a born crusader. In some ways you remind me of Nathan." She looked away for a moment. "But I haven't always marched to a crusader's rhythm. I was quite content as a chain-smoking psychotherapist, until three years ago. Then I had my reinforced revelation." She coughed again. "I found out I had lung cancer."

Hilan had met Jan just a year ago, through another of his rare crusader friends, who had just discovered the Institute. He'd wondered briefly about her past, about why she molded the Institute into a national resource that did all the things it was famous for--from seminars on mass media, to job matching, to weapon systems development--but he hadn't thought about it enough. Now it was obvious.

"The chemotherapy they have these days is quite terrific. They can keep you alive and active, even while the cancer is eating you up inside. Then the end comes quite suddenly." She closed her eyes. "Leslie and Nathan both insisted I shouldn't challenge the mountain this last time. I guess they were right."

Hilan stared with helpless horror.

"We'll find a hospital in the morning. Better get some sleep--we'll start early."

The ache deep within his bones allowed him no other response. He slept, but his sleep roiled with odd images: images of Soviets, and cigarettes, and nuclear missiles. Woven through them all were images of a man, dangling in a crevasse, with only the strength of the rope and the taut determination of his partner's straining muscles to save him.

SNAP. In games of ball and racket, such as tennis, the racket must cease to be a separate external object. It must become one with the player--an extension of his arm. The arm and the eye must also meld through the mediation of the mind. And though the mind controls this connection, it too must submerge its separateness, its awareness of self, into the union. Only the racket connected directly to the eye plays outstanding tennis.

CLICK. With the acquisition of the flatcam video recorder, the news reporter develops a similar relationship with his camera. With the tape riding quietly on his hip, and the flat camera lens pinned on his lapel, individual virtuosos can repiace the old-style news teams. The camera is almost invisible; the reporter is quite inconspicuous. As he becomes less conspicuous, he becomes less inhibiting to the people who are his targets. The reporter's eye and the reporter's camera become a single device with which to capture the images he will later clean and craft in the lab. The lab supplies the magic. It is a place where background noise and foreground lighting can be toned to highlight the message, all by using powerful techniques of Information Age filtering.

WHIR. Bill Hardie knows that he has been born in the right moment of history--the beginning of the era flatcam journalism. He can see from the camera lens in his lapel--not merely the lighting and the people, but the action, the emotions, the sensations. He can zero in on those elements with the skill of an astronomer picking out galaxies on the edge of the universe. Sometimes he can sense the critical moment, allowing him to shift his attention before the event, to capture its very beginnings, rather than its concluding passage.

JUMP. The only flaw in Bill's coverage is an occasional jerkiness to the image, a reflection of a certain anxious impatience with real life. His analysis is too important to wait on the sluggish motions of other men. Fortunately, the jitter of his camera, like the noise of murmured voices in the background, can be removed in the laboratory.

FOCUS. Bill recognizes the heavy burden his talent places on him. He understands his mission in life. He must broadcast truth in a pure form to all people. Just as his computer filters the background noise that blurs the coversation, he must filter out the foreground noise that blurs the fundamental reality.

BREAK. Bill frowns at the young geological engineer from the Zetetic Institute up on the stage. The engineer poses a serious problem for Bill. This engineer introduces blaring noise into the foreground, drowning out the truth. The truth is: The people of the State of Washington must not let the United States dump its radioactive wastes there. Nuclear power plants and radioactive wastes are bad; this is the truth. Bill focuses his attention on the nuances of the situation, to wring victory from every tiny image as it happens.

SHADE. Three men sit spotlighted on the stage facing a dimly lit auditorium. Cigarette smoke forms miniature weather inversions here and there in the audience. A puff of acrid blue haze blows across Bill's face; he shifts locations.

FOCUS. The spotlights create the mood of an interrogation, with unseen prosecutors and accusers contemplating the three men nearly blinded by the light. The Zetetic engineer sits in the middle of the three, flanked by two older men--directors from the Power Commission. These directors are the ones who had hired the Zetetic Institute to act as an impartial consultant, to assess the safety of a radioactive waste storage facility near Hanford, Washington.

Why had they hired the Institute? They had known that the Institute had a reputation for doing good engineering. Equally important, the Institute had a reputation for presenting that engineering smoothly in public.

Indeed, the opening of the discussion is dry and crisp, almost too civilized; the Zetetic engineer simply presents facts about the geological properties of the proposed waste site. With careful clarity, he shows why it is a safe place to put radioactives. Bill realizes the Power Commission has taken a risk in hiring the Institute: Zetetics search diligently facts, and facts could go against the Power Commission as easily as they could go in its favor.

The men of the Power Cemmission, in their dark blue suits, with their tight, closed faces, mirror the audience's hostility. They perform as perfect Establishment objects of disdain. Had the engineer sat to the side rather than in the middle of the trio, Bill would zoom on them and construct a crisp image of Good versus Evil--the audience versus the Power Commission.

But the engineer sits in the middle, looking gentle, even friendly, in his light blue suit and solid red tie. He maintains an open smile and equally open eyes, apparently oblivious to the emotional tension that stews amidst the combatants. Only the careful precision of his words hints that his understanding of the situation goes deep. Bill will have to perform magic with the lighting and the shading of the stage to make him look sinister. Even then, Bill's success will be incomplete.

PAN. Ovals of pale white float in the darkness of the auditorium: the faces of the concerned citizens who live near Hanford. From here the questions spring, randomly, in sharp tones of frustration and anger. One oval bobs twice, then rises. It is a young woman with spiked hair and mottled jeans. She asks, "How can we make them shut those plants down if we let them dump their waste products on our land?"

When the engineer responds to the woman's question, his voice warms the room with its honesty. "The best way to eliminate nuclear power is, of course, to find a better form of power, such as fusion or solar power satellites. Remember, if you just tell the Power Commission that they can't build nuclear power plants, without telling them what would be better, they'll probably build a coal-burning plant. Is that really better?" The engineer shrugs. "That's a separate study, of course."

ZOOM. For just a moment, the young man frowns. Bill mtches that expression, savoring it, knowing it will be useful. "This is the safest place we can find to put the wastes that already exist. In other words, if we put them someplace else, it's more dangerous. Many of you are concerned about how dangerous nuclear reactors are. Don't you see that if you won't let the power companies use the safest methods they can find, then you are creating a self-fulfilling prophecy? Do you believe that you should sabotage the reactors to show how dangerous they are? That is exactly what a person does when he prevents others using safety precautions."

WHIR, WHIR, WHIR. This is beautiful! Bill can use that bit about sabotage: it will make the engineer sound hostile, despite the suit cheer of his voice.

PAN. A middle-aged man with a beard and a faded flannel shirt speaks, arms crossed, from a slouched position in his seat. "We have the right to decide what to put outside our town."

SLIDE. The engineer nods. "That's true." His smile freezes in position as he looks into the speaker's eyes. "You; have the right to decide. But living in a democracy is not just a matter of rights and freedoms; it is also a matter of responsibilities and duties. You have the right to shout 'Fire!' in a crowded theater. You have a duty to not exercise that freedom.

"Similarly, here you have the right to decide. But you have a duty to make that decision based on the most caueful, rational analysis of the facts that you can. You have a duty not to decide based on a general hatred for the Power Commission, as some people might. And you have a duty not to decide on the basis of a love of high technology, as other people might."

CLIP. A voice from the darkness shouts, "It's not fair that it all goes in our backyards."

ROLL. The engineer sighs. "Our society carries with it a number of undesirable features. The only fairness we can approach is to spread the unfairness as fairly as we can. Let them put the radioactives here; it's the best place. But make them put the missile silos and the strip mines elsewhere. If someone figures out another arrangement that's as safe as putting the radioactives here, but that's more fair, and that doesn't have any other even more serious consequences, let's do that instead."

ZOOM. Another middle-aged man stands. This one wears a suit that might have done justice to a member of the Power Commission. "What about our property values? When they put that radioactive dump in our backyards, we'll-be destroyed."

SLIDE. Another nod comes from the engineer. "Of course, if the Power Commission handles the waste properly, the property values should not be affected. So to encourage them, we recommend that the Commission be required to pay the owner of a property the diiference between the value of the land considering the presence of the site, and the value of the land if the site weren't here, when he sells. We've subcontracted with a real estate assessor to establish a set of baseline values." He glanced sideways at the Commission men with a hint of amusement. "This was not the recommendation that the Commission liked most."

PAN. An elderly lady rasps from the front, "What if they don't handle the wastes properly? What if they make a mistake?"

ZOOM. Sorrow masks the Zetetic's face for a moment. "That's what we must prevent. As I've shown, there are a wide veriety of mistakes that the system can tolerate because the base rock of the area is fundamentally safe. And the shipping containers are also safe from a wide variety of human errors and natural calamities. But ultimately, even this system must rely human beings to not invent new kinds of errors. So we asked ourselves the following question: What mechanism could we use to inspire the operators of the site to seek out and correct unforeseen probllems before they become critical?"

The young man smiles as he contemplates the probing analysis he has done on this problem. "Do you know how the Romans guaranteed the quality of their bridges? In the opening ceremony, the men designed the bridge floated on a underneath while the first carts passed over. If the bridge collapsed, the builder of the bridge went with it. This ritual guaranteed the construction of many good bridges."

CUT. This story gets a short, murmured chuckle from the audience, as if against their own will, they appreciate the justice of the system.

SLIDE. The Zetetic engineer waves an open hand. "We have a similar plan here, involving both a carrot and a stick. For the stick, we recommend that the chief operating engineer and the plant manager for the waste site be required to live within twenty miles of the site during their tenure.

"We also recommend protection for engineer. If he finds grave hazards with the plant that he cannot fix because of expense or politics, then he can blow the whistle with security: The Power Commission will be required to pay him five years' salary. Thus, the man in the best position to know about new dangers has a 'parachute' to protect him from the people who have the most to lose in fixing the problem."

PAUSE. The audience seems struck by this approach to guaranteeing safety. They don't know if it will work or not, but at it is at least different; Even Bill feels a stab of surprise. He clenches his teeth with resolve, remembering that even this novel idea does not change the basic truth.

FLASH. A woman in the back, with two children squirming beside her, speaks. "Are you telling us that the danger from these radioactive wastes is zero?"

PAN. "Of course not," the engineer replies, leaving Bill with a wave of relief. He can certainly use that reply for some mileage. "What I'm tellin you is that the danger from the radioactive dump is less than the danger of driving your car home tonight."

CUT. The discussion goes on, but to no purpose in Bill's value system. Most of the people leave with the same opinions they held upon arrival. But Bill knows that the engineer, with his facts, has swayed some of those people away from the truth. Herein Bill sees the significance of his own life: He must bring those people back to the fold, and convert others--enough others to defeat the damned Zetetic Institute.

Indeed, the Institute, and its emphasis on facts represent a grave danger to more issues other than the Hanford waste storage debate. Bill sees a task of greater scope facing him. Perhaps part of his purpose is to destroy the purveyors of such facts, facts that by denying truth become a travesty of truth.

CUT. CUT. CUT. CUT. The size of the editing job he faces with this video shakes him; the Zetetie engineer has been smooth indeed. The engineer qualifies as a politician, despite his early recitations on ground waiter, earthquakes; and mining costs. However, that smoothness does not worry Bill unduly: after all, whoever gets the last word wins the argument. And in news reporting, the editing reporter always gets the last word.

WRAP.

Yuri Klimov decided that it was the ivory figurines that lent the cold formality to the room. The shiny figurines glared at him from their perches in the shiny black bookcases. Despite their carefully kept luster, however, they were old. Age had worn them to soft curves in a thousand little places meant for sharply carved angles. Age had worn them as age had worn the General Secretary himself, seated across the mahogany table from Yurii.

General Secretary Sipyagin closed his eyes. Yurii feared he might have dozed off, but his eyes opened again, in a slow, blinking motion. His pallid skin folded into a smile. "Delightful, Yurii. I am pleased you have found the Americans easy to deal with."

Yurii shrugged. "Mayfield has little choice but to yield. His people practically advertise their need for paper assurances. All we need do is squeeze," he closed his fist ever so gently, "and concessions flow forth." He smiled. "Mayfield got into office by promising to relax worldwide tensions. He must sign, and sign, and sign again to maintain his position."

"Nevertheless, you handle him like a master. Now, a few years ago when we tried negotiating with Keefer and his henchmen things were very different.

"The secret is to be able to think as the Americans think--without losing our Soviet pragmatism." He shook his head, and spoke with just a hint of puzzlement. "They do not think like us, you know.

Sipyagin coughed in a sound of disgust. "Yes. They think like weak children."

Yurii opened his mouth to object, then closed it. "Yes, often like children."

"We'll start a new missile program immediately. When those crazy Americans were toying with space defenses it was a bad investment to build missiles--who knew what kind of countermeasures we might have to retrofit? At last, we've been relieved of this burden of uncertainty."

Yurii smiled. "Yes, now we can sharpen our strategic edge."

Sipyagin gurgled with laughter. "As if we needed to sharpen it any more."

Yurii joined the laughter. It was wonderful, sharing a joke with the General Secretary, despite his infirmities. Or perhaps because of them. "With this treaty, it will be easy to maintain our strategic advantage. It might make more sense at this point to start undermining their tactical forces. I'll see what my men can do in the next round of discussions."

Sipyagin nodded. "A marvelous idea." He turned away to look at a stack of wrinkled papers by his side

Clearly the General Secretargr had dismissed him, but Yurii had one more request. "Sir, there is one last thing I would like to investigate in the strategic realm."

"Yes?"

"I question this whole cencept of global consequences for a nuclear war. I know that our modellers agree with their modellers: you can set off just so many megatons before the radiation releases and the climate are so massive that they span the planet, no matter where they get set off. But many of those modellers are soft civilians, who want us to avoid nuclear warfare for their own reasons. I can't help wondering if the threshold might be higher than these people think. Simulation is a soft science, as I'm sure you know. Its results should not be left in the hands of biased civilians. If we knew that the threshold were higher, we would have an enormous edge over the Americans; we could continue barraging them with nuclear weapons even after they had ceased fire. Living in their fantasy world of nuclear danger, they would fear killing their own surviyors:

The General Secretary chuckled. "Control of a nuclear war would belong completely to us then, wouldn't it? Very well." He waved his hand--was it shaking?--toward the door. Yurii felt Sipyagin's weary eyes follow him as be swept through it.

Yutii breathed deeply. The air in the hall was stale, but he felt refreshed nonetheless. Interviews with the General Secretary always reminded him how wonderful it was to be young and healthy.

Copyright © 1988 by Marc Stiegler

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details